In the midst of her controversy with the London pastor William Huntington over the gospel and the law, the Particular Baptist authoress and hymn writer Maria de Fleury made a telling point.

She rightly noted: ‘Angry passions and bitter words ought never to be brought into the field of religious controversy; they can neither ornament nor discover truth, but they can grieve and quench that Holy Spirit, in whose light alone we can see light, and without whose divine illuminations, we shall walk in darkness.’

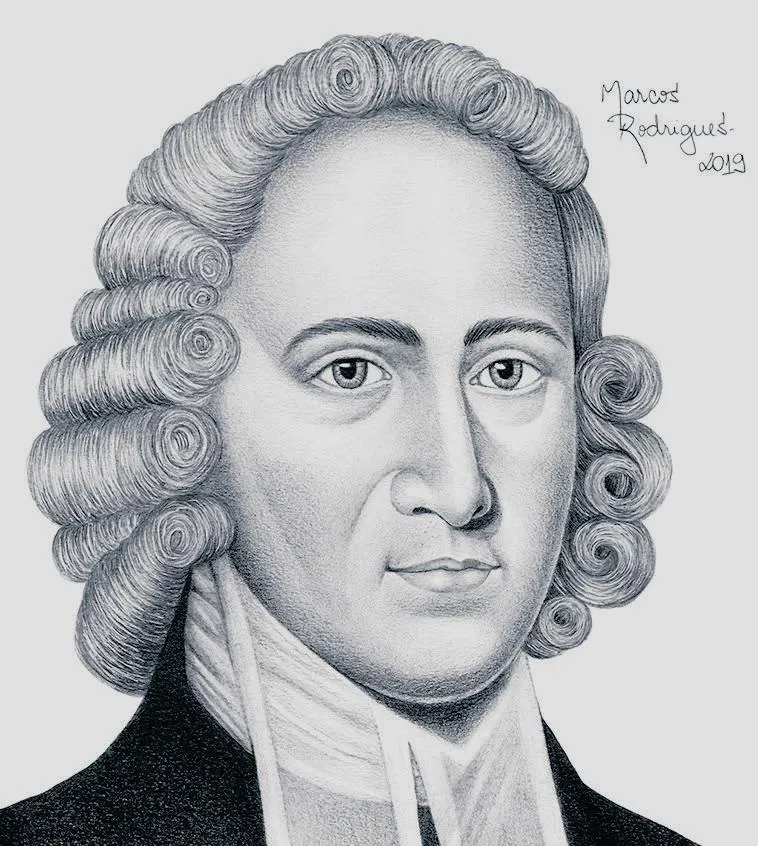

This consciousness of the danger of controversy – the way that it engendered ‘angry passions’ harmful to the soul and fed into ‘bitter words’ that made deep emotional wounds and gashes in the souls of others – was a consistent theme in the best evangelical writers of the 18th century. One only has to read the writings of men like Jonathan Edwards, the American Congregationalist divine who once rebuked the great evangelist George Whitefield for unwise public comments about those who disagreed with the Great Awakening, as well as the Anglican John Newton, and his protégé, the Particular Baptist John Ryland, to see this. It was a long-held maxim of Ryland, for instance, ‘never to dispute with the infallible’, a reference to men who prided themselves on never having changed their minds on non-essential issues and who were utterly resistant to persuasion.

The Jewishness of the Gospels proves they're true

When speaking to Jewish and Gentile friends you might have heard the accusation that the Gospel accounts were written centuries …