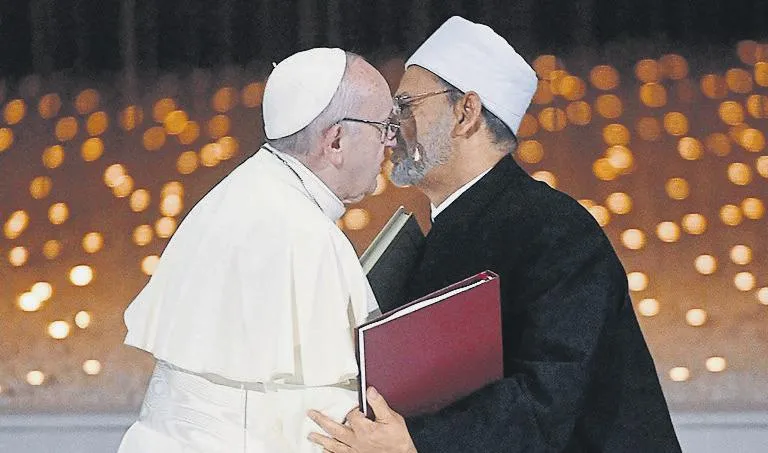

It has been rightly called the ‘political manifesto’ of Pope Francis’ pontificate.

In fact, there is a lot of politics and a lot of sociology in the new encyclical All Brothers, a very long document (130 pages) that looks more like a book than a letter. Francis wants to plead the cause of universal fraternity and social friendship. To do this, he speaks of borders to be broken down, of waste to be avoided, of human rights that are not sufficiently universal, of unjust globalisation, of burdensome pandemics, of migrants to be welcomed, of open societies, of solidarity, of peoples’ rights, of local and global exchanges, of the limits of the liberal political vision, of world governance, of political love, of the recognition of the other, of the injustice of any war, of the abolition of the death penalty. These are all interesting ‘political’ themes which, were it not for some comments on the parable of the Good Samaritan that intersperse the chapters, could have been written by a group of sociologists and humanitarian workers from some international organisation, perhaps after reading, for example, Edgar Morin and Zygmunt Bauman.

Much politics, little theology

These are the themes that Pope Francis has disseminated in many speeches and in his other encyclical, Laudato si (2015), on the care for the environment. Not surprisingly, he himself is by far the most cited author in the work (about 180 times),which evidences the circular trend of his thinking (the need to be self-strengthening) and the ‘novelty’ of his teaching with respect to the traditional themes of the social doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church. The vision proposed by All Brothers is the way in which Rome sees globalisation – with the eye of a Jesuit and South American pope.